What Can A Place Name Reveal About Its History?

- Posted in:

- Heritage

- Miner2Major

Miner2Major focuses on the heart of the Sherwood Forest area from Nottingham to Ollerton, and Mansfield to Rufford Abbey, an area that has a distinctive landscape character. Just like archaeological sites, historical sites, monuments and historic buildings, the landscape is an integral part of the historic environment. Place names establish identity and assist communications, but historic maps show us that place names change through time. How do these changes help us unravel history?

Place names can tell us stories that would otherwise be unknown. Often made up of two elements, a prefix and a suffix, the names can be decoded to reveal natural features that may have disappeared, ownership or the character and origins of a settlement. Through the centuries, place names have evolved, reflecting historical, linguistic, and cultural changes. The evolution of place names is called Etymology.

Anglo-Saxon Names

Many names are rooted in Old English, the Germanic language that was brought to England by the Anglo-Saxons, and in-use between the mid-5th to 12th centuries. Anglo-Saxon place names take different forms. Some refer to people or animals in the prefix, followed by a suffix that denotes ownership. Examples include Blidworth, probably meaning Blida’s Farm, and Ravenshead, high ground named after the bird or a man bearing that name. Others refer to the landscape, ending in ‘field’ (Mansfield) or ‘ley’ (a clearing), (Annesley).

Settlements and towns were given names ending in ‘ham’, ‘tun’ or ‘ton’ (Ollerton). A fortified town is indicated by the suffix ‘burh’ ‘brough’ ‘borough’, ‘burgh’ or ‘bury’, for example the hamlet of Brough, built around a Roman military settlement.

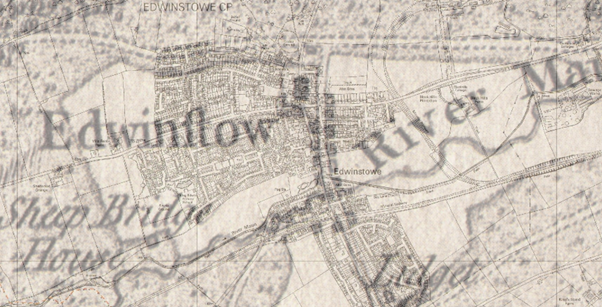

Places with a religious connection often end in ‘minster’ or ‘stow’. Edwinstowe is documented in the Domesday Book of 1086 as ‘Edenestou’. The name commemorates the legend of the body of King Edwin of Northumbria, being laid to rest near here after he was killed in battle in 632. Many other spellings occur over the centuries Hedenestoua (1173), Edenestowa (1194), Eddenstowe (1287); Edwynstow (1300); Edenstow (1577); Eddingstowe (1633).

Above: Modern Edwinstowe overlying Chapman’s map of 1774.

Viking Names

The Viking settlers of the 9th and 10th centuries left their mark on the Nottinghamshire landscape, with place names ending in ‘by’, the Danish word for town, or ‘thorp’ meaning settlement of Danish people. Examples of these include Walesby, Budby, Bilsthorpe and Perlethorpe. The prefix of the name can also reveal clues about the landscape. Linby for example, means Lime Town and’ Kirk’ indicates a church (Kirkby and Kirklington).

The Domesday Book

The first large-scale survey of England was commissioned by William the Conqueror in 1086. The Domesday Book was a comprehensive survey of the land and resources in England to be used as a tool for taxation and governance. This was probably the first time place names in Nottinghamshire were officially written down. The Norman surveyors were French speakers and whenever they encountered a tricky name, they simplified it and recorded a variation that was easier for French speakers. Sometimes they added ‘bel’ or ‘beau’ as a prefix (Beauvale).

Maps

One of the oldest maps of the area was drawn by Joan Blaeu in 1646. Most of the names are recognisable, but the spelling of place names in maps and documents continued to vary due to mispronunciation and inconsistent spelling. Several variations of a name might be in use at the same time. It was not until the first Ordnance Surveys in the 1840s that the spelling of place names became standardised.

Above: Joan Blaeu Map, 1646. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland CC_BY (NLS). Visit the Blaeu Atlas here: Map

Place names are still not set in stone. Some place names are relatively new where new settlement or industry occurs, and some do change. Clipstone and King’s Clipstone are good examples. King’s Clipstone is recorded in the Domesday Book (1086) as ‘Clipestune’. King Edward I, bestowed the prefix King ‘Kyngesclipston in 1290, after parliament was held at King John’s Palace. As its importance declined, it became simply known as Clipstone, then Old Clipstone as the new Clipstone Colliery village grew in the 1920s. In 2011, the community chose to reinstate the medieval name of Kings Clipstone to create a distinct identity separate from the colliery village of Clipstone.

Above: Kings Clipstone shown as ‘Clipstone’ on Sanderson’s map of 1835.

Place Name Etymology in the Miner to Major Landscape Partnership Area.

Below are other examples of place name etymology in the Miner to Major project area, recording the name changes as shown on dated maps or documents.

Wellow - First attested in 1207 in pipe rolls as Welhag’. Also, Welagh (1316), Wellehach’ (1250); Wellhawe (1275); Whellay (1494); and finally, Wellow in 1747. The word is a compound word from Old English: wielle and haga, referring to an enclosure of some kind near to a spring. A small tributary of the Maun is nearby and could refer to that.

Blidworth - First attested in the Domesday book in 1086 as Bliedeworde. Also, Blieswurda (1158); Blithewurth (1240); Blittewrth (1271); Blideth (1670). Blieworth probably means “Blida’s Farm”.

Annesley - First attested in the Domesday book in 1086 as Aneslei. Also, Anisleia (1190); Anyslegh (1250); Ansley (1590). Possibly a compound of a personal name An with Leah (meaning An’s clearing).

Linby - First attested in 1086 in Domesday book as Lidebi. Also, Lindebeia (1316); Linneby (1233); Lundeby (1304); Lynby (1392). From Old Norse linda býr, meaning “lime-tree village”.

Bestwood -First attested in 1177 as Beskewuda in the pipe rolls. Also, Beescwde (1200); Buskwud (1207); Bekeswood (1523); and finally, Bestwood in 1619. From Old English bēosuc, a derivative of the Old English word bēos(e), meaning bent grass (how Beeston also gets its name). Therefore, Bestwood means “wood where bent grass grows” in Old English.

Ollerton - First attested in the Domesday Book in 1086 as Alretun. Also, Allerton (1276); Alverton (13th c.); and Ollerton by 1316. From the words alor and tun, meaning “farm of the alders”.

Papplewick - First attested in the Domesday book in 1086 as Paplleuuic. Also, Papelwich (1316); Papewich’ (1165); and Papleweeke. Formed from the words pappol(stan) and wic, meaning “dairy farm in the pebbly place” in Old English. As noted by some researchers, some fields on the east side of the village are very pebbly.

Ravenshead - First attested in 1205 as Ravenesheved. Literally means “Raven’s Head” It is the highest ground in the neighbourhood and the hill may have been so called from the bird or from a man bearing that name.

Newstead - “New Place”. The place obtained its name at the time of the foundation of the Austin Priory here by Henry II.

Warsop - Domesday book 1086 as Wareshope. Also, Wyrssop (1321-4); Worsoop (1569); Warsopp Church towne, Warsopp Markett towne (1653). The second element of the word is hop, “valley”, the well-marked valley between the two settlements at Church and Market Warsop being the determining factor in the original settlement. Warsop means “the Valley of Wǣr” (Wǣr being an Old English personal name).