Archaeology Using Aeroplanes!

- Posted in:

- Archaeology

- NewsletterArchive

This wonderful articles comes from our Summer 1999 Heritage Newsletter:

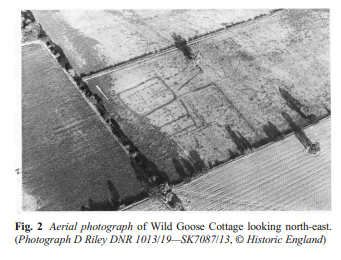

The summer months are an appropriate time to catalogue the air photograph collection held in the HER. Cropmarks appearing in the fields of the county at this time of year can add greatly to our knowledge of Nottinghamshire’s past. Often these cropmarks reveal sites and features that cannot be discovered through other types of investigation. Cropmarks show as variations in colour which highlight areas where the crop has grown or ripened at different rates. So how have peoples’ activities created these cropmarks?

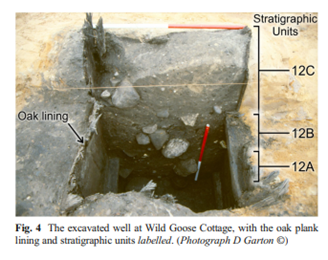

There are two types of cropmark that can form (see illustration above). In the first case, a buried feature, such as the remains of a wall or foundations of a building, can affect the make up of the soil in that area and cause it to be better drained. This means that the crops in this area are receiving less water than those in the rest of the field. Therefore, they grow slower and ripen quicker. These buried features show as yellow lines of ripe crop in an otherwise unripe green field.

Secondly, features cut into the ground, such as ditches and pits, usually retain more moisture than the rest of the surrounding crop due to the nature of the material that has filled the features over time. The material washed into the holes tend to contain more organic material than the surrounding soil and so holds more moisture. This means that the crops will grow quicker in the spring and show as darker green lines in a green field. Then, as the crop ripens in the summer, the plants over the ditches have more water and are later to ripen, showing as green lines in ripe cereals.

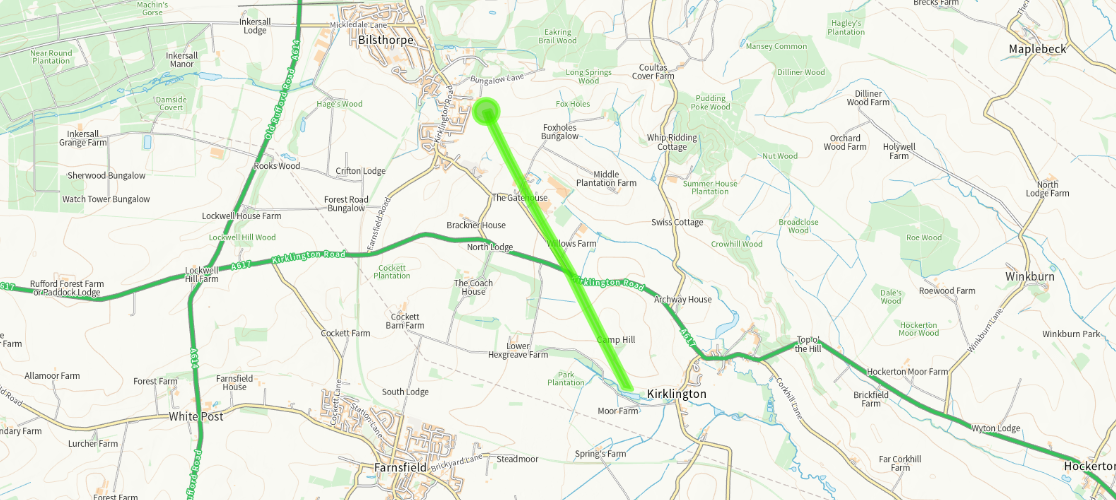

Cropmarks can give us a wealth of information about archaeology of many different periods. Aerial photographs of cropmarks in the Muskham area, for example, show vast areas of land marked out with complex field system and possible settlement sites that may date from the Iron Age and Roman periods. We would know a great deal less about the county’s past if it were not for this perspective from the air.