Previously Unrecorded Archaeological Features Discovered Within Strawberry Hill Nature Reserve

- Posted in:

- Heritage

- Archaeology

- Miner2Major

Strawberry Hill is a Nottinghamshire Wildlife Trust (NWT) nature reserve, and up until recently, records within the nature reserve and surrounding area were scarce, with no recorded archaeological work having been carried out on site before. The scarcity of records is likely a result of the extensive mineral extraction activities which were carried out before archaeological considerations were drawn into the planning process. There is a wealth of documentary evidence that indicates Strawberry Hill was once a significant landscape feature and way-marker.

Strawberry Hill has been a significant feature in the landscape since Medieval times and it appears, under different names, on numerous historic maps as well as Medieval perambulation documents. It sits on the historic boundary between the land of the abbots of Rufford and the land of the King’s manor of Mansfield.

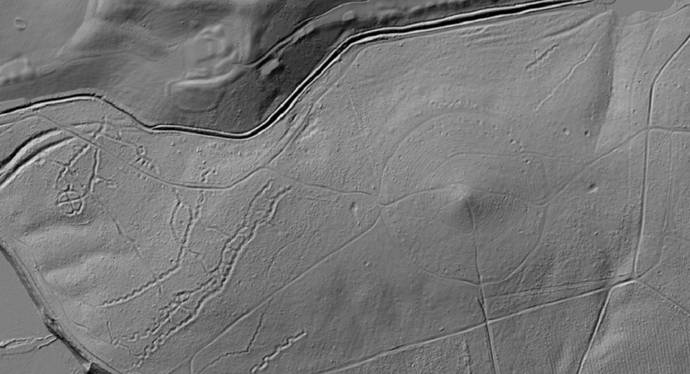

Recently, as part of the Miner 2 Major Veiled Landscape project, the area was subject to an archaeological survey, where NWT volunteers and a Nottinghamshire County Council archaeologist used lidar data to help guide the on-the-ground recording of previously unrecorded archaeological features. This survey enhanced our knowledge of the presence and significance of archaeological features and resources within the woodland.

Above: LiDAR model showing earthworks within Strawberry Hill Nature reserve.

Several hollow ways survive within the woodland, one set of which is a well-used Medieval routeway that went out of use some time in the post-Medieval period. These are sections of deeply eroded ‘U’ shaped hollow ways that almost certainly represent a Medieval routeway between Mansfield and Bilsthorpe, which passes by Inkersall on the north side of the dam. This appears on the 1637 map of the Rufford Estate drawn by Bunting. Given the significance of the hill here in the landscape, historically it is possible that some of the other recorded hollow-ways may have significant age to them.

Above: Nottinghamshire Wildlife Trust volunteers and Nottinghamshire County Council archaeologist Emily Gillott standing in the contours of the Medieval hollow way.

There is also a well-preserved set of practice trenches from army training activities from the earlier 20th century This is part of a wider landscape that is characteristic of this part of Nottinghamshire, as many of the large estates turned over some of their land to military usage. Many classic features of the trench warfare system are apparent including the classic zig-zag plan and communication lines dug to connect parallel trench sets.

You can explore these records and the lidar survey data by searching in the database for the records below:

-

MNT27659: Military training trenches in Strawberry Hill wood

-

MNT27660 - Military pits and dugouts in Strawberry Hill wood

You can learn more information about the Veiled Landscape Project and the application of lidar here: The Veiled Landscape: Sherwood Lidar Project - Nottinghamshire Historic Environment Record