Remarkable Mansfield

- Posted in:

- Heritage

- NewsletterArchive

This lovely article comes from our Winter 1999 Heritage Newsletter:

Quoting from Celia Fiennes, the trouble with Mansfield is that ‘there is nothing remarkable here’, an opinion echoed by a later commentator, Roy Christian who remarked that it is a ‘pity that this quite pleasant town that has had a market since 1277…should have so few distinguished buildings, though its locally quarried white and red sandstone has added distinction to such buildings elsewhere as the Houses of Parliament and St. Pancras Station’. There is, however, evidence to counter such views not only in the buildings that unfortunately have gone but also in those that are still standing. We shall look at one building in Mansfield and see what made it remarkable.

The Mansfield Public Baths were erected in 1853 near the corner site of Bath Street and Littleworth. Even though they have been demolished, it is fitting that they have been replaced by the Water Meadows Swimming Centre, thereby continuing the watery theme! They were built by the architect C.J. Neale and builder C. Lindley, when the population of England was steadily increasing, with a major growth in the population of England and Wales from around 8 million at the beginning of the century to over 32 million towards the end. The building was constructed from a local material, the grey Mansfield stone which was used in the building of the Houses of Parliament, as Roy Christian pointed out.

Barbara Gallon has given us a fascinating insight into how the original baths served the public before replacement by the modern version. Their purpose was arguably more important in that they provided facilities which the majority of the patrons would not have possessed. Baths and showers could be had at varying costs depending on the class of ‘cleaning’ required, as well as whether towels were hired out or not (with the charge of 3d for the pleasure) and the time of day one went for one’s toilet. For example, first class warm bath and use of warm towels cost 6d, whereas second class use cost 4d, whilst cheapest of all was a third class bath with only one towel provided for 2d. for using the swimming pool, 1d or 2d was charged depending on the time of day. The entrance hall was reputedly quite spacious, with the ladies’ area running off to the right and divided into first and second class bathing area. The gentlemen’s section was to the left of the entrance hall, again offering different classes of bathing.

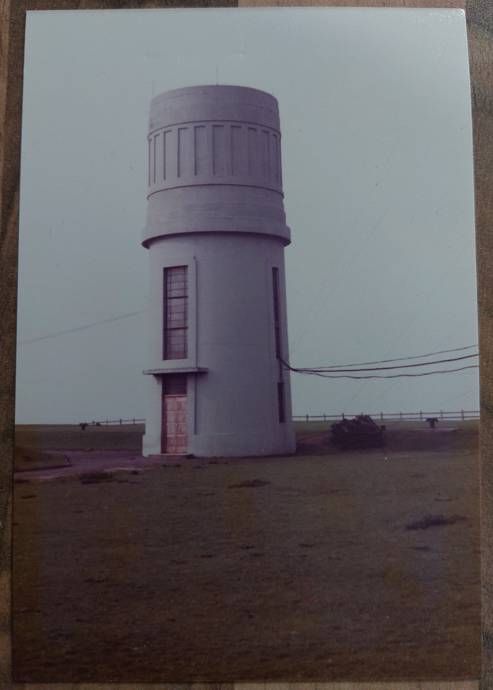

The photograph shows how the building looked in August 1969, markedly changed – four decorative chimney stacks had been removed and modern windows replaced the stone mullioned originals. Ornate iron railings used to flank the building, only the wall gate piers remain as evidence of their former glory.